Citizenship Status and Family Ties in the Context of Sentencing Federal Drug Offenders

Federal Drug Sentencing Laws Bring High Cost, Low Return

Penalty increases enacted in 1980s and 1990s have non reduced drug use or backsliding

Overview

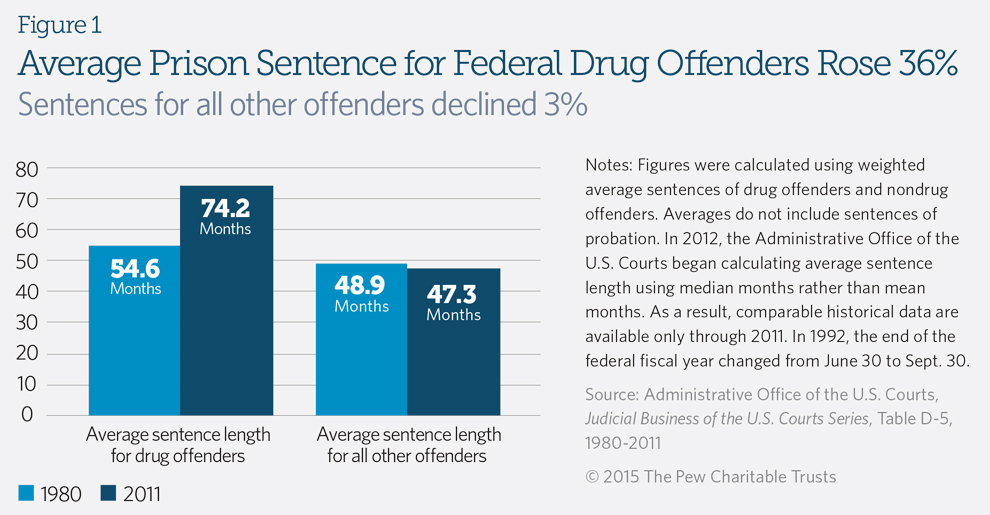

More than 95,000 federal prisoners are serving time for drug-related offenses—up from fewer than 5,000 in 1980.1 Changes in drug crime patterns and law enforcement practices played a role in this growth, but federal sentencing laws enacted during the 1980s and 1990s also have required more drug offenders to go to prison— and stay in that location much longer—than iii decades ago.ii (See Figure ane.) These policies have contributed to ballooning costs: The federal prison system now consumes more than $half dozen.vii billion a year, or roughly 1 in 4 dollars spent past the U.South. Justice Section.iii

Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers take not realized a strong public condom return. The cocky-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term every bit drug prices have fallen and purity has risen.4 Federal sentencing laws that were designed with serious traffickers in listen have resulted in lengthy imprisonment of offenders who played relatively small-scale roles.v These laws likewise take failed to reduce recidivism. Nearly a third of the drug offenders who get out federal prison and are placed on community supervision commit new crimes or violate the conditions of their release—a charge per unit that has non inverse substantially in decades.6

More than imprisonment, college costs

Congress increased criminal penalties for drug offenders during the 1980s—and, to a lesser extent, in the 1990s—in response to mounting public business organisation about drug-related criminal offence.7 In a 1995 report that examined the history of federal drug laws, the U.S. Sentencing Commission constitute that "drug abuse in general, and scissure cocaine in detail, had go in public opinion and in members' minds a trouble of overwhelming dimensions."8 The nation's violent crime charge per unit surged 41 pct from 1983 to 1991, when it peaked at 758 trigger-happy offenses per 100,000 residents.9

Congress increased drug penalties in several ways. Lawmakers enacted dozens of mandatory minimum sentencing laws that required drug offenders to serve longer periods of confinement. They too established compulsory sentence enhancements for sure drug offenders, including a doubling of penalties for echo offenders and mandatory life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for those convicted of a third serious offense. These laws have practical broadly: Every bit of 2010, more than 8 in 10 drug offenders in federal prisons were convicted of crimes that carried mandatory minimum sentences.10

Besides during the 1980s, Congress created the Sentencing Commission, an appointed panel that established strict sentencing guidelines and mostly increased penalties for drug offenses. The aforementioned police that established the commission, the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, too eliminated parole and required all inmates to serve at least 85 percent of their sentences backside bars earlier becoming eligible for release.

Federal data show the systemwide effects of these policies:

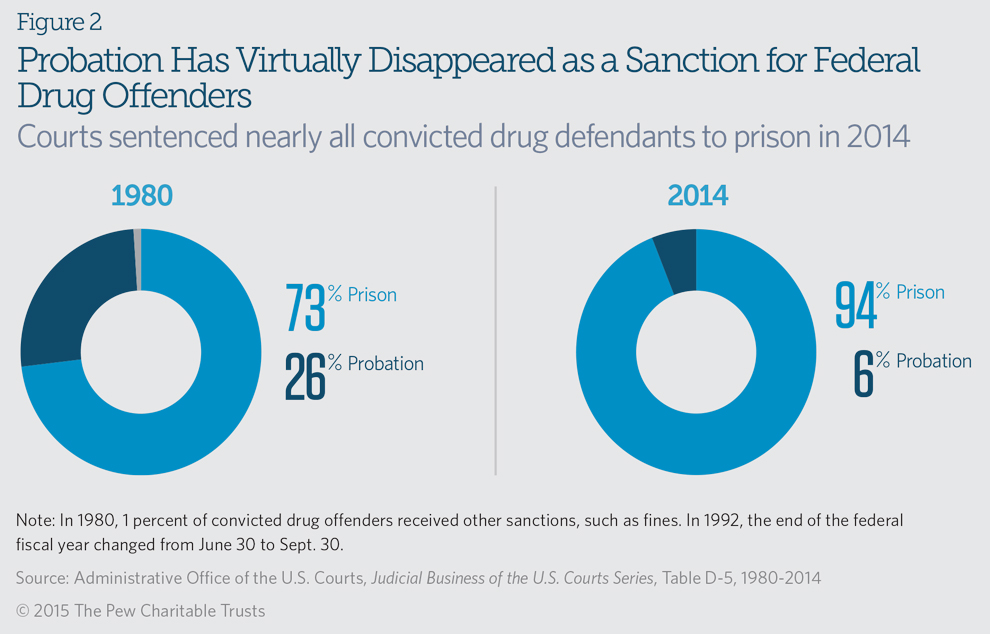

- Probation has all merely disappeared as a sanction for drug offenders. In 1980, federal courts sentenced 26 pct of convicted drug offenders to probation. By 2014, the proportion had fallen to half-dozen percent, with judges sending nearly all drug offenders to prison.11 (Run into Figure two.)

- The length of drug sentences has increased sharply. As shown in Effigy 1 above, from 1980 to 2011 (the latest year for which comparable statistics are available), the average prison sentence imposed on drug offenders increased 36 percent—from 54.6 to 74.2 months—even as it declined three percent for all other offenders.12

- The proportion of federal prisoners who are drug offenders has nearly doubled. The share of federal inmates serving fourth dimension for drug offenses increased from 25 percent in 1980 to a high of 61 percent in 1994.13 This proportion has declined steadily in recent years—in role because of ascension prison admissions for other crimes—just drug offenders all the same correspond 49 percent of all federal inmates.14

- Fourth dimension served by drug offenders has surged. The average time that released drug offenders spent behind confined increased 153 percent between 1988 and 2012, from 23.2 to 58.6 months.15 This increase dwarfs the 39 and 44 per centum growth in time served past property and vehement offenders, respectively, during the same period.16

The increased imprisonment of drug offenders has helped drive the explosive overall growth of the federal prison house system, which held nearly 800 percent more inmates in 2013 than it did in 1980.17 One study found that the increase in time served by drug offenders was the "single greatest contributor to growth in the federal prison population betwixt 1998 and 2010."18

Growth in the prison population has driven a parallel surge in taxpayer spending. From 1980 to 2013, federal prison spending increased 595 percent, from $970 million to more than $6.seven billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.19 Taxpayers spent well-nigh as much on federal prisons in 2013 as they paid to fund the entire U.S. Justice Department—including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and all U.S. attorneys—in 1980, after adjusting for aggrandizement.20

Increased availability and use of illegal drugs

Measurements of the availability and consumption of illegal drugs in the United states of america are imprecise. Users may be reluctant to share information near their illegal behavior, and national surveys may not capture responses from specific populations—such as homeless or incarcerated people—who may have loftier rates of drug use. Drug markets also vary considerably from metropolis to city and land to country, and amid different drugs.

Despite these limitations, the best available data suggest that increased penalties for drug offenders—both at the federal and state levels—have not significantly inverse long-term patterns of drug availability or employ:

- Illegal drug prices have declined. The estimated street price of illegal drugs is a commonly cited mensurate of supply. Higher prices indicate scarcity while lower prices suggest wider availability. Afterwards adjusting for inflation, the estimated retail prices of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine all decreased from 1981 to 2012, even as the purity of the drugs increased.21

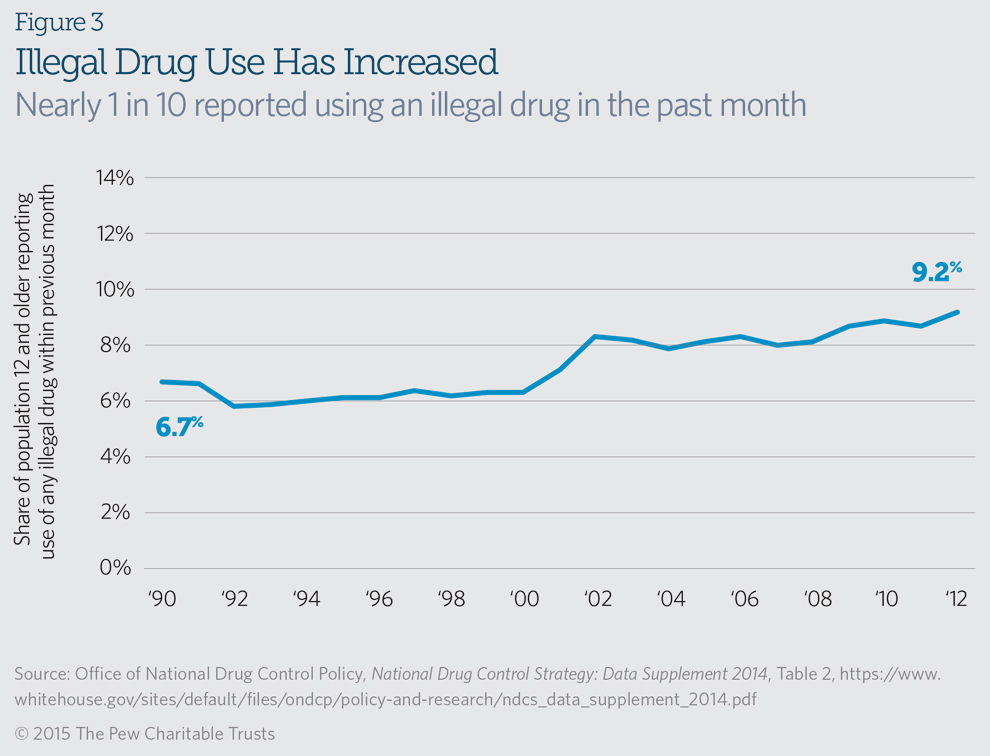

- Illegal drug use has increased. The share of Americans historic period 12 and older who said in a national survey that they had used an illicit drug during the previous month increased from half dozen.7 percent in 1990 to 9.ii percent—or nearly 24 million people—in 2012.22 (Encounter Figure three.) An increase in marijuana use helped drive this trend, more than offsetting a turn down in cocaine use.

Just equally enhanced criminal penalties have not reduced the availability or use of illegal drugs, research shows that they are unlikely to significantly disrupt the broader drug trade. 1 report estimated that the chance of existence imprisoned for the sale of cocaine in the U.S. is less than 1 in xv,000—a prospect so remote that information technology is unlikely to discourage many offenders.23 The same applies for longer sentences. The National Research Council ended in a 2014 report that mandatory minimum sentences for drug and other offenders "have few if any deterrent effects."24 Even if street-level drug dealers are apprehended and incarcerated, such offenders are easily replaced, ensuring that drug trafficking tin go on, researchers say.25

To be certain, many criminologists agree that the increased imprisonment of drug offenders—both at the federal and country levels—played a office in the ongoing nationwide decrease in crime that began in the early 1990s. But research credits the increased incarceration of drug offenders with only a 1 to 3 per centum decline in the combined tearing and property crime charge per unit.26 "Information technology is unlikely that the dramatic increment in drug imprisonment was cost- effective," one study ended in 2004.27

Penalties do non lucifer roles

The federal regime is responsible for combating illegal drug trafficking into the United States and across state lines. Equally a result, traffickers represent the vast majority of the drug offender population in federal prisons.28 Federal sentencing laws have succeeded in incarcerating kingpins and other serious drug offenders for whom prison is the advisable option. At the same fourth dimension, however, they have resulted in the lengthy imprisonment of many offenders who played relatively pocket-sized roles in drug trafficking.

The Anti-Drug Corruption Act of 1986 demonstrates this trend. The law established a five-year mandatory minimum judgement for "serious" drug traffickers, defined every bit those bedevilled of crimes involving a minimum corporeality of illegal drugs, including 100 grams of heroin or 500 grams of cocaine. The law also created a 10-yr mandatory minimum sentence for "major" traffickers—those convicted of crimes involving larger amounts, including 1 kilogram of heroin or v kilograms of cocaine.29 Nether the law, mandatory minimum sentences double from five to 10 years—and from 10 years to 20—for second offenses.

Although the law was intended to separate offenders into lower and higher degrees of culpability based on the amount of drugs involved in their crimes, these distinctions accept not ever captured individuals' truthful roles in drug distribution networks. "The quantity of drugs involved in an law-breaking is not as closely related to the offender'southward role in the crime equally perhaps Congress expected," the Sentencing Committee concluded in a special report to Congress in 2011.thirty

The quantity of drugs involved in an criminal offense is not as closely related to the offender'southward function in the offenseas perhaps Congress expected. U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2011

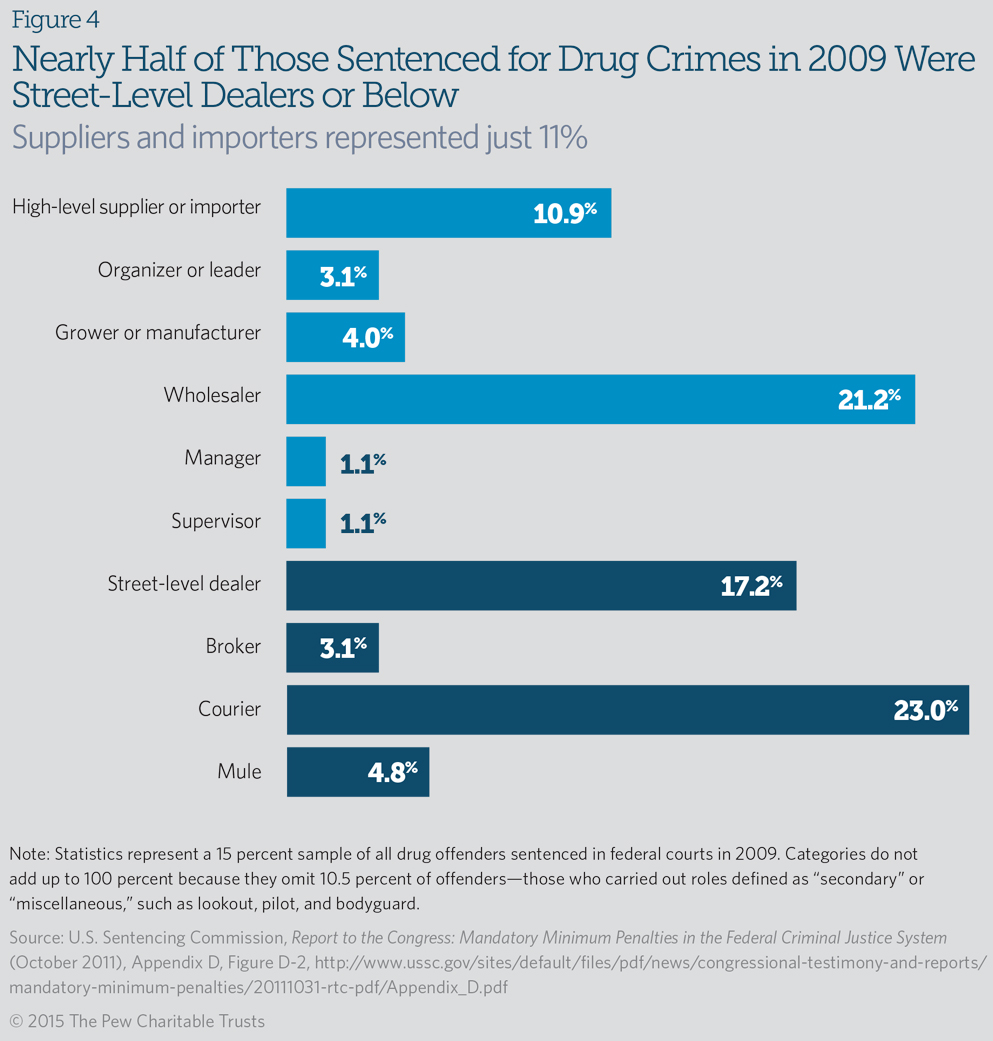

Historical data limitations make information technology difficult to appraise whether the drug traffickers incarcerated in federal prisons today are more or less serious than those of three decades ago. But the Sentencing Commission's report underscores that federal resources have not been directed at the virtually serious drug traffickers.31 According to the report, in 2009:

- Those sentenced for relatively minor roles represented the biggest share of federal drug offenders. More than than a quarter of federal drug offenders—and two-thirds of federal marijuana offenders—were "couriers" or "mules," the lowest-level trafficking roles on a culpability scale adult by the commission.32 (Meet Figure iv.) The average sentences for couriers and mules—defined as those who send illegal drugs either in a vehicle or on their person—were 39 and 29 months, respectively.

- Nearly a 5th of federal drug offenders were street dealers. Offenders divers as "street-level dealers"—those who distributed an ounce or less of illegal drugs straight to users—made up 17 percent of federal drug offenders and about half of federal crack cocaine offenders.33 The average judgement for these individuals was 77 months.

- The highest-level traffickers represented a insufficiently small share of federal drug offenders. Those defined as "loftier-level suppliers" or "importers"—the top function on the culpability scale—represented 11 percentage of federal drug offenders. The average sentence for these offenders was 101 months.

- Judgement lengths did not always marshal with offenders' functions. Although lower-level functionaries by and large received much shorter average sentences than higher-level offenders, there were notable exceptions: Midlevel "managers," for case, received an average sentence of 147 months, or nearly four years longer than the 101-month average sentence imposed on the highest-level traffickers.

It is important to note that federal law permits two exemptions to mandatory minimum sentences that frequently benefit many lower-level drug traffickers.34 One allows judgement reductions for those who provide prosecutors with "substantial assistance" during the form of an investigation. The other, known as the "condom valve," applies to offenders who meet five specific criteria, including a limited criminal history and a nonleadership role in the drug trade.

Although these sentence reduction tools are intended to—and generally do—benefit depression-level traffickers the most, in that location are exceptions. More than one-half of offenders deemed to be high-level suppliers or importers, for instance, received relief from mandatory minimum penalties in 2009, compared with less than a third of those classified as street-level dealers—despite the much lower culpability level of the latter grouping.35

Post-prison outcomes unchanged

Research has institute little relationship between the length of prison terms and backsliding rates mostly—a design that holds among drug offenders at the federal level.

Of the more than 20,000 federal drug offenders who concluded periods of mail-release community supervision in 2012 (the latest year for which statistics are available), 29 percent either committed new crimes or violated the conditions of their release.36 This proportion has changed little since the mid-1980s, when sentences and time served began increasing sharply.37

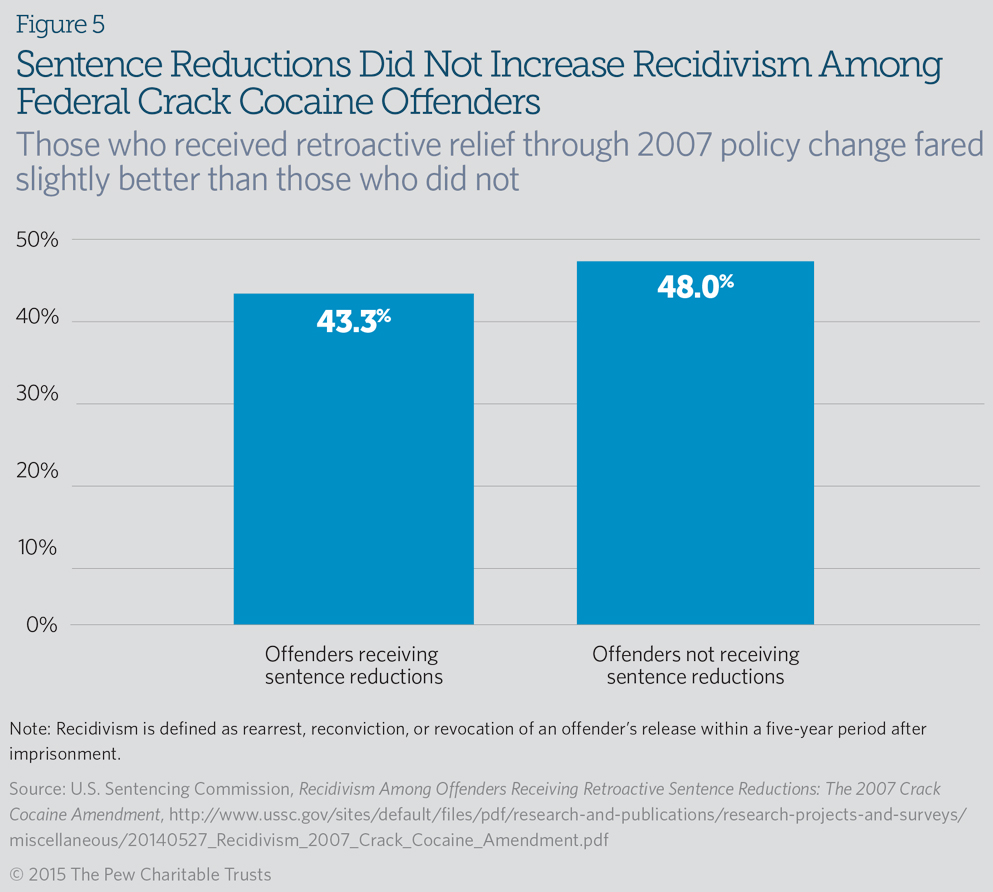

Conversely, targeted reductions in prison terms for certain federal drug offenders have not led to college recidivism rates. In 2007, the Sentencing Committee retroactively reduced the sentences of thousands of crevice cocaine offenders.38 A follow-up study on the furnishings of this modify plant no show of increased recidivism amid offenders who received sentence reductions compared with those who did non.39 (Meet Figure 5.) In 2010, Congress followed the Sentencing Commission's actions with a broader, statutory reduction in penalties for scissure cocaine offenders.

Timeline

Conclusion

The federal government has a uniquely important part to play in the fight against the illegal drug merchandise: Information technology is responsible for preventing the trafficking of narcotics into the U.s. and beyond country lines. In response to rising public concern nigh loftier rates of drug-related crime in the 1980s and 1990s, Congress enacted sentencing laws that dramatically increased penalties for drug crimes, which in plow sharply expanded the number of such offenders in federal prison and drove costs upward. These laws—while playing a role in the nation's long and ongoing crime decline since the mid-1990s—have not provided taxpayers with a potent public safety return on their investment.

The availability and use of illegal drugs has increased even as tens of thousands of drug offenders accept served lengthy terms in federal prisons. Recidivism rates for drug offenders have remained largely unchanged.

Meanwhile, federal sentencing laws that were designed to focus penalties on the virtually serious drug traffickers accept resulted in long periods of imprisonment for many offenders who performed relatively minor roles in the drug trade.

In response to these discouraging trends, federal policymakers recently take fabricated administrative and statutory revisions that have reduced criminal penalties for thousands of drug offenders while maintaining public safety and controlling costs to taxpayers.

Endnotes

- For the electric current effigy, run into "Inmate Statistics - Offenses," Federal Bureau of Prisons, accessed June 29, 2015, http://world wide web.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp. For the 1980 figure, see University at Albany, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 2003, Table 6.57, http://www.albany.edu/sourcebook/pdf/t657.pdf.

- Nathan James, The Federal Prison Population Buildup: Overview, Policy Changes, Issues, and Options (Washington: Congressional Inquiry Service, 2014), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42937.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Federal Prison System Shows Dramatic Long-Term Growth" (February 2015), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/Assets/2015/02/ Pew_Federal_Prison_Growth.pdf.

- Part of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy: Information Supplement 2014, Tables 1 and ii, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/ndcs_data_supplement_2014.pdf. Pew used the 1990-2012 menstruation to capture all available yearly data.

- U.S. Sentencing Commission, Written report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (October 2011), Chapter 8, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Chapter_08.pdf.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Justice Statistics Statistical Tables Serial 2005-2012, Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics Serial 1984- 2004, http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=65.

- U.South. Sentencing Commission, Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System, Chapter 2, http://www.ussc.gov/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/special-report-congress.

- U.S. Sentencing Commission, Report on Cocaine and Federal Sentencing Policy, Chapter half-dozen, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/report-cocaine-and-federal- sentencing-policy-2.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, Uniform Crime Reporting data tool, http://www.ucrdatatool.gov.

- U.Due south. Sentencing Committee, Written report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice Arrangement (October 2011), Chapter eight, 165, http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Chapter_08.pdf.

- Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Judicial Business of the U.Southward. Courts Series, Table D-5, 1980-2014, http://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/analysis-reports/judicial-concern-united-states-courts. The 1980 report is available in print merely. In 1992, the end of the federal fiscal year inverse from June thirty to Sept. xxx.

- Authoritative Office of the U.South. Courts, Judicial Business of the U.S. Courts Series, Table D-5, 1980-2011. The 1980 report is available in print only. Figures calculated using weighted average sentences of drug offenders and nondrug offenders. Average does not include sentences of probation. In 2012, the Administrative Office of the U.Due south. Courts began calculating average judgement length using median months rather than mean months. As a consequence, comparable historical data are available only through 2011. In 1992, the end of the federal fiscal year inverse from June 30 to Sept. 30.

- University at Albany, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 2003, Table 6.57, http://world wide web.albany.edu/sourcebook/pdf/t657.pdf.

- "Inmate Statistics - Offenses," Federal Bureau of Prisons, accessed June 29, 2015, http://world wide web.bop.gov/nigh/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

- For the 1988 figure, encounter Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Criminal Case Processing, 1982-93, Tabular array xviii, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/Fccp93.pdf; for the 2012 effigy, see Agency of Justice Statistics, Federal Justice Statistics 2012—Statistical Tables, Table 7.11, http://world wide web.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fjs12st.pdf. Pew used the 1988-2012 menses to capture all bachelor yearly data.

- Ibid.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Federal Prison System Shows Dramatic Long-Term Growth."

- Kamala Mallik-Kane, Barbara Parthasarathy, and William Adams, "Examining Growth in the Federal Prison Population, 1998 to 2010" (September 2012), Urban Establish, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412720-Examining-Growth-in-the-Federal-Prison-Population--to--.PDF.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Federal Prison System Shows Dramatic Long-Term Growth."

- Ibid.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy: Data Supplement 2014, Tables 66, 67, and 68, https://world wide web.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/ndcs_data_supplement_2014.pdf.

- Office of National Drug Command Policy, National Drug Command Strategy: Data Supplement 2014, Tables 1 and 2, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-inquiry/ndcs_data_supplement_2014.pdf. Pew used the 1990-2012 flow to capture all available yearly data.

- David Boyum and Peter Reuter, An Analytic Assessment of U.S. Drug Policy, American Enterprise Establish for Public Policy Research (2005), 57, http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/-an-analytic-assessment-of-united states of america-drug-policy_112041831996.pdf.

- National Enquiry Quango, The Growth of Incarceration in the United states: Exploring Causes and Consequences (2014), 83, http://www.nap.edu/itemize/18613/the-growth-of-incarceration-in-the-united-states-exploring-causes.

- Mark A.R. Kleiman, "Toward (More than Nearly) Optimal Sentencing for Drug Offenders," Criminology & Public Policy 3, no. 3 (2004): 435–440, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6taQDF0rdAwYnJNTDU2bDVBNFU/edit.

- Ilyana Kuziemko and Steven D. Levitt, "An Empirical Analysis of Imprisoning Drug Offenders," Journal of Public Economics 88 (2004): 2043–2066, https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/ikuziemko/papers/kl_jpube.pdf.

- Ibid.

- U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2014 Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics, Table 12, http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/annual-reports-and-sourcebooks/2014/Table12.pdf.

- U.Due south. Sentencing Commission, Study on Cocaine and Federal Sentencing Policy, Chapter half dozen, http://www.ussc.gov/report-cocaine-and-federal-sentencing-policy-2.

- U.S. Sentencing Committee, Report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (Oct 2011), Chapter 12, 350, http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Chapter_12.pdf.

- Unless otherwise indicated, all information about offender roles are drawn from U.Southward. Sentencing Commission, Report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (October 2011), Appendix D, Figure D-two, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Appendix_D.pdf; and Figure 8-12, 173, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Chapter_08.pdf.

- For share of marijuana offenders considered mules or couriers, run across U.Southward. Sentencing Committee, Written report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (October 2011), Appendix D, Effigy D-34, http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Appendix_D.pdf.

- For share of crack cocaine offenders considered street-level dealers, see U.South. Sentencing Committee, Report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (October 2011), Appendix D, Effigy D-22, http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Appendix_D.pdf.

- Charles Doyle, "Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentences: The Safety Valve and Substantial Help Exceptions" (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2013), https://www.hsdl.org/? view&did=746019.

- U.South. Sentencing Commission, Report to the Congress: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System (Oct 2011), Chapter viii, 170, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/mandatory-minimum-penalties/20111031-rtc-pdf/Chapter_08.pdf.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Justice Statistics 2012—Statistical Tables, Table 7.5, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fjs12st.pdf.

- Agency of Justice Statistics, Federal Justice Statistics/Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics Series, 1984-2012, http://www.bjs.gov/alphabetize.cfm?ty=pbtp&tid=65&iid=1. Information non available for 1987, 1991, 1992, and 2005.

- U.Southward. Sentencing Commission, "U.S. Sentencing Commission Votes Unanimously to Use Subpoena Retroactively for Crack Cocaine Offenses" (Dec. 11, 2007), http://www.ussc.gov/news/printing-releases-and-news-advisories/december-11-2007.

- Kim Steven Hunt and Andrew Peterson, "Recidivism Among Offenders Receiving Retroactive Sentence Reductions: The 2007 Crack Cocaine Amendment" (May 2014), U.S. Sentencing Commission, http://world wide web.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-projects-and-surveys/miscellaneous/ 20140527_Recidivism_2007_Crack_Cocaine_Amendment.pdf.

ADDITIONAL Resources

MORE FROM PEW

mcmilloncamle2002.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2015/08/federal-drug-sentencing-laws-bring-high-cost-low-return

0 Response to "Citizenship Status and Family Ties in the Context of Sentencing Federal Drug Offenders"

Post a Comment